Deux poèmes inédits de Sappho

An “Oxford secret” is supposed to be a secret you tell one person at a time. Add social media and it’s across the world within hours, often in garbled form. In this case, the “secret” was the discovery on a fragment of papyrus of two new poems by the seventh-century BC Greek poetess, Sappho. The first concerns her brothers, “The Brothers Poem” for short. The second, “The Kypris Poem”, is about unrequited love and addressed to Aphrodite (by her other name, “Kypris”). The full evidence will be presented in an article in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (2014), and I am grateful to the editors Jürgen Hammerstaedt and Rudolf Kassel for permission to publish some preliminary facts here, and to raise some key questions: why is the discovery important, what do the poems tell us about Sappho, and how do we know they are genuine?

An “Oxford secret” is supposed to be a secret you tell one person at a time. Add social media and it’s across the world within hours, often in garbled form. In this case, the “secret” was the discovery on a fragment of papyrus of two new poems by the seventh-century BC Greek poetess, Sappho. The first concerns her brothers, “The Brothers Poem” for short. The second, “The Kypris Poem”, is about unrequited love and addressed to Aphrodite (by her other name, “Kypris”). The full evidence will be presented in an article in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (2014), and I am grateful to the editors Jürgen Hammerstaedt and Rudolf Kassel for permission to publish some preliminary facts here, and to raise some key questions: why is the discovery important, what do the poems tell us about Sappho, and how do we know they are genuine?

One important implication does not concern Sappho at all – but vindicates the historian Herodotus, who mentions a poem in which she criticized her brother Charaxos or his mistress. A trader in Lesbian wines, he conceived a passion for a notorious courtesan then a slave in Egypt, and ransomed her at a great price, at which Sappho gave vent to her indignation in a song. Although Herodotus’ account is retold by several later authors, the very existence of Charaxos in Sappho’s poetry has been doubted by many scholars. In “The Brothers Poem” (below) a speaker addresses someone, criticizing this person for always chattering about “Charaxos” coming with a full ship, instead of leaving such things to the gods; and it closes by wishing that Larichos (whom we know from elsewhere as a brother of Sappho) might grow up to be a man, and so bring joy in place of sorrow.

The identity of the addressee who chatters incessantly “Charaxos came” (or perhaps “comes”, or “may come”) is unknown, since the text as we have it begins at least a stanza or two into the poem. But it gives us a firm attestation for Charaxos (even though not explicitly called “brother”), and strongly suggests that Herodotus did in fact draw on earlier poetry for his historical evidence. It also gives a glimpse into Sappho’s family drama under the boom-or-bust economic conditions of international trade in the “Archaic Age” and the pressures of inheritance, marriage and class.

But how does the poem fit into Sappho’s known work? What we seem to have is, like others in her oeuvre, a prayer (for the safe return of the merchant-gone-to-sea) embedded in a song. It suggests performance on some ritual occasion. Here a prayer for the safe return expands to envisage what such a return would mean for the family. And there may be literary, Homeric, echoes too: Charaxos might be seen as an Odysseus figure (with Larichos as a potential Telemachos) in a family drama with epic overtones; if so, then Sappho herself evokes the figure of Penelope.

Yet some critics have already been unimpressed with its poetic quality. Martin West, for example, commented that “The poem is not one of her most poignant: as I see it, we have a young Sappho, perhaps still a teenager, addressing her mother and worried about their domestic circumstances”; others have cautiously concluded that it is not her best poem. Is this fair?

Probably not. So far from frigid juvenilia, the verses show an ear for balancing and texture, the pulse of rhythm, graceful shaping of words, and an atmospheric ending to a poem. Echoes of “The Brothers Poem” in Latin poets certainly suggest that they found it memorable: Ovid has Sappho say that she “advised” her brother “extensively” with good intentions, freely, but with pious speech (hoc mihi libertas, hoc pia lingua dedit). This looks like the frank speech (verging on the colloquial in “chattering”) of “The Brothers Poem”, combined with its pious hymnic discourse. So far from jejune, its proverbial wisdom was thought worthy of adaptation (as Gregory Hutchinson points out) in Horace’s “Soracte Ode”:

permitte diuis cetera, qui simul

strauere uentos aequore feruido

deproeliantes, nec cupressi

nec ueteres agitantur orni.

(Leave everything else to the gods, who in a moment still the winds when they do battle on the raging sea, and neither the cypresses nor the old ash trees are blown around.)

What might seem like cliché or conventional wisdom in the central section of “The Brothers Poem” has expressive point in its mere assertion, just as gnomic statements in Pindar or at the end of a Greek tragedy do. Here they form part of the articulation of a lyric narrative, one that shifts almost imperceptibly from the envisaged distress that sparks the prayer to the envisaged happiness that comes with the prayer’s fulfilment. The desired good becomes more specific or personal in the end, and may (as often in Sappho’s poems) include or imply marriage. Many will find the last two stanzas, in particular the last two lines, especially moving, with their sisterly exhortation to Larichos to go and play a Telemachos-like role and show himself “a man”, while the heavy and rare word βαρυθυμία – “weightiness of spirit”, “depression”, raising the stylistic level, correlates with the devastating erotic love we find elsewhere in Sappho. Here she is the devoted sister, worrying about her younger brother, as in other poems she does about girls, one of whom (after all), if he lifts his head, Larichos will grow up to marry. In another she is the mother of “darling Kleis, my beautiful child who looks like golden flowers”, who is worth more to her than all Lydia.

“The Kypris Poem” that follows in the new papyrus is less well preserved and in various places harder to reconstruct. But it returns to the subject of erotic love, filling out into near-complete verses what were previously only a few letters per line in another papyrus (“Frag. 26”), and showing where previous reconstructions went wrong:

“How could one indeed not repeatedly feel

anguish

Queen Kypris, over whomever one really

wanted to make one’s own?”

This powerful opening invocation parallels the recurrent onslaught of unrequited desire dramatized by the appeal to the goddess in Sappho’s famous “Hymn to Aphrodite” (“Frag. 1”), and it makes the indefinite object of desire its defining focus, as in the “what one loves” of “Frag. 16” (“Some say a troop of horses . . . is the finest thing on earth, but I say it is what one loves”).

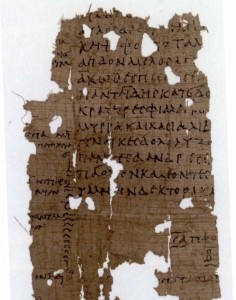

But how can we be certain that such resemblances are authentically Sapphic and that these new fragments are genuine? After all, you might wonder, doesn’t “The Brothers Poem” rather too conveniently fill a gap in what we know of Sappho and her family? And doesn’t it rather suspiciously confirm Herodotus, in mentioning two names we know, and none that we don’t? Palaeography provides a criterion, but also a model for forgers. Some scholars did, at first, doubt its authenticity, including one of the editors of the last “New Sappho” to be discovered. But other indicators leave no room for doubt. Metre, language and dialect are all recognizably Sapphic and (more difficult for a forger to achieve) there are no contrary indications whatsoever of date or handwriting. The authorship of Sappho was clinched, however, when the papyrus’s text was found to overlap, in two narrow vertical bands of letters, with fragments of two previously published papyri containing fragments of Sappho.

The antiquity of the physical fabric of the papyrus is beyond reproach: indeed, it was damaged in ancient times, torn up the centre of the one complete surviving column, and still bears the ancient papyrus repair strips on its back applied in antiquity. It is written in black carbon ink in an identifiable professional bookhand, but with idiosyncratic stylistic traits that would be difficult for a modern calligrapher consistently to emulate. It also passes tests of spectral analysis for density of ancient carbon-base ink. The authenticity of the ancient mummy cartonnage panel, from which the papyrus was extracted, having been recycled in antiquity to accompany a burial, has been established through its documented legal provenance. The owner of the papyrus wishes to remain anonymous, but has submitted the papyrus to autopsy and multi-spectral photography, as well as Carbon 14 testing of an uninscribed portion of the papyrus sheet itself by an American laboratory, that returned a date of around 201 AD, with a plus-minus range of a hundred years.

The antiquity of the physical fabric of the papyrus is beyond reproach: indeed, it was damaged in ancient times, torn up the centre of the one complete surviving column, and still bears the ancient papyrus repair strips on its back applied in antiquity. It is written in black carbon ink in an identifiable professional bookhand, but with idiosyncratic stylistic traits that would be difficult for a modern calligrapher consistently to emulate. It also passes tests of spectral analysis for density of ancient carbon-base ink. The authenticity of the ancient mummy cartonnage panel, from which the papyrus was extracted, having been recycled in antiquity to accompany a burial, has been established through its documented legal provenance. The owner of the papyrus wishes to remain anonymous, but has submitted the papyrus to autopsy and multi-spectral photography, as well as Carbon 14 testing of an uninscribed portion of the papyrus sheet itself by an American laboratory, that returned a date of around 201 AD, with a plus-minus range of a hundred years.

The remarkable thing is that both new texts – damaged as they are – read almost as though they were complete poems today, partly due to the unique qualities of a poet who cannot have foreseen her poetry’s survival in fragmentary form. “The Brothers Poem” may have been intended to be seen or heard by Charaxos and Larichos themselves. But private as it is, it can still welcome and engage the modern reader, and it adds an important piece to the jigsaw that is Sappho and her work.

The Brothers Poem; translated by Christopher Pelling

[. . .]

ἀλλ’ ἄϊ θρύλησθα Χάραξον ἔλθην

νᾶϊ σὺν πλήαι. τὰ μέν οἴομαι Ζεῦς

οἶδε σύμπαντές τε θέοι· σὲ δ᾽οὐ χρῆ

ταῦτα νόησθαι,ἀλλὰ καὶ πέμπην ἔμε καὶ κέλεσθαι

πόλλα λίσσεσθαι βασίληαν Ἤραν

ἐξίκεσθαι τυίδε σάαν ἄγοντα

νᾶα Χάραξονκἄμμ’ ἐπεύρην ἀρτέμεας. τὰ δ’ ἄλλα

πάντα δαιμόνεσσιν ἐπιτρόπωμεν·

εὐδίαι γὰρ ἐκ μεγάλαν ἀήταν

αἶψα πέλονται.τῶν κε βόλληται βασίλευς Ὀλύμπω

δαίμον’ ἐκ πόνων ἐπάρωγον ἤδη

περτρόπην, κῆνοι μάκαρες πέλονται

καὶ πολύολβοι·κἄμμες, αἴ κε τὰν κεφάλαν ἀέρρη

Λάριχος καὶ δή ποτ᾽ ἄνηρ γένηται,

καὶ μάλ’ ἐκ πόλλαν βαρυθυμίαν κεν

αἶψα λύθειμεν.[. . .]

Oh, not again – ‘Charaxus has arrived!

His ship was full!’ Well, that’s for Zeus

And all the other gods to know.

Don’t think of that,But tell me, ‘go and pour out many prayers

To Hera, and beseech the queen

That he should bring his ship back home

Safely to port,And find us sound and healthy.’ For the rest,

Let’s simply leave it to the gods:

Great stormy blasts go by and soon

Give way to calm.Sometimes a helper comes, if that’s

The way Zeus wills, and guides a person round

To safety: and then blessedness and wealth

Become one’s lot.And us? If Larichus would raise his head,

If only he might one day be a man,

The deep and dreary draggings of our soul

We’d lift to joy.

(cet article est paru originellement dans le Times Literay Supplement du 5 février 2014. A lire également l’article du Temps).

(« Dernier vers des Noces d’Hector et d’Andromaque de Sappho », papyrus d’Oxyrhynque ; « Sappho et Alcée« , 1881, huile sur toile de Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Walters Art Museum)